Jun 02,2021

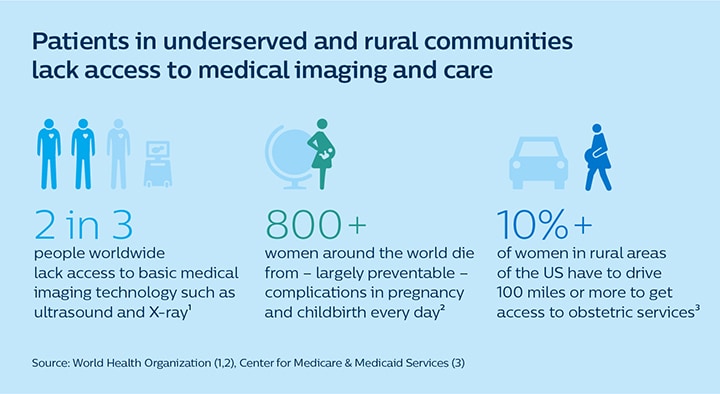

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that two-thirds of the world’s population lack access to basic medical imaging technology, causing preventable and sometimes fatal delays in diagnosis and treatment [1]. What if we could bridge those gaps in care – virtually?

Every day, more than 800 women around the world die from complications in pregnancy and childbirth. Although most of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, maternal mortality rates in developed nations such as the US tell an equally sad story, with women in rural areas being affected disproportionately hard [2,3]. Tragically, many of these deaths could be prevented – if only those women had access to a routine ultrasound check-up that would bring complications to light earlier [4].

And this example doesn’t stand alone.

Having access to medical imaging technology – whether it’s a basic ultrasound or an X-ray exam, or more advanced modalities like CT and MR – can make the difference between life and death. Just consider the countless lives that have been saved with routine mammography and lung screening exams alone.

Yet today, two-thirds of the world’s population lack access to even basic imaging technology. Even in those underserved regions where the technology is available, what’s often lacking are enough skilled hands to operate it, and experienced eyes to interpret the findings. Patients, on their part, may be deterred by long and expensive trips to the nearest healthcare facility; with safety concerns posing another barrier in times of COVID-19. The result: delayed testing, diagnosis, and treatment, with increased downstream costs for healthcare systems and increased risk of adverse outcomes for patients.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

For patients in remote and underserved communities as well as the healthcare providers that struggle to serve them, there’s new hope on the horizon. We can now bring better care to patients – through virtual collaboration that supports local staff from a distance. Here’s what that looks like.

Remote education brings expert care to local communities

The WHO recommends that every pregnant woman should undergo at least one ultrasound scan, preferably in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, to accurately estimate gestational age, detect fetal anomalies, and improve a woman’s overall pregnancy experience. But in the vast rural areas of Kenya, where trained ultrasound specialists are in short supply and pregnant women may have to travel for many hours to the nearest hospital, that guidance is still a far cry from reality.

That’s why the Philips Foundation, together with local clinical partners and the Ministry of Health, is bringing portable ultrasound into the hands of trained midwives at primary care facilities, while connecting them to experienced specialists in urban hospitals. Through a combination of in-person training, remote education, and real-time video collaboration, the midwives can build the skills and confidence to perform routine basic obstetric screening themselves. This allows them to provide better care and identify high-risk women for timely treatment at an appropriate healthcare center, giving those women a much better chance of bringing a healthy child into the world.

And the virtual collaboration doesn’t end there. It is part of a full digital ecosystem of connected care, in which all relevant patient data – including lab tests and ultrasound data – can be shared across locations for remote diagnostic assistance and monitoring.

Using a simple mobile app, midwives can build a health profile of pregnant women by collecting data from physical exams at primary care facilities or even at the soon-to-be-mom’s home. From this data a risk score is generated, which can help caregivers identify women who need extra care. On top of that, expecting moms can engage in their own care through an educational app that delivers pregnancy-related tips. The app also allows them to track data such as kick count, pregnancy symptoms, and medication usage – and to share that data with caregivers for an even more complete picture.

Through this cloud-based model, authorized obstetricians and gynecologists are able to keep a caring eye on patients from any location.

A digitally integrated maternal care ecosystem allows doctors, midwives, and community healthcare workers to share patient data and consult each other virtually for remote diagnostics

The Philips Foundation has piloted elements of this approach with Amref Health Africa’s Amref International University in Kenya, and is now working with Aga Khan University Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health to assess its impact on clinical outcomes more systematically. Initial experiences are highly encouraging, showing how trained midwives in primary care facilities – with the right remote support – can play an integral role in early detection, diagnosis, and follow-up of pregnancy and pregnancy-related complications. As an additional advantage, because all patient data is shared digitally, it leaves less of a paper trail, making it a more environmentally friendly approach too. Everyone benefits.

Midwives at rural health clinics in Kenya can now conduct basic ultrasound exams in pregnant women and share data remotely for virtual collaboration (Photos: Amref Health Africa)

What’s exciting about this kind of remote education model is that it’s not just a temporary band-aid. It elevates local knowledge and skill levels to help improve access to care in an enduring and sustainable way, right where it’s needed, in the heart of communities.

In the same spirit, the Philips Foundation has provided emergency medicine physicians in US hospitals with a platform to train their peers in Peru in the use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) – through live virtual collaboration. Trained physicians in Peru have since become local champions who leverage their learnings beyond their own practice by educating colleagues. During the pandemic, these local champions have also taken a leading role in using POCUS to support diagnosis and treatment guidance for COVID-19 patients.

Hear more about this cross-continental collaboration in the video below:

Tele-ultrasound meets patients where they are

In developed nations such as the US, imaging expertise may be more widely available – but it is often unevenly distributed across urban and rural divides. And this problem is only bound to get worse. For example, in maternal care, it is estimated that the shortage of highly skilled obstetricians, gynecologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (MFMs) in the US will increase more than threefold between 2020 and 2050, with shortages becoming increasingly acute in rural areas. Already today, more than 1 in 10 rural women in the US have to drive 100 miles or more to get access to obstetric services [3].

Virtual collaboration can be part of the solution here, too. Using a live collaboration platform integrated into an ultrasound system, an experienced sonographer in a city hospital can remotely assist their local counterpart with an ultrasound exam, while an MFM specialist can use the same platform to discuss the patient’s medical status with her. It no longer matters whether the patient is sitting in the room next to him, or in a clinic at the other end of the state. Virtually, the MFM specialist is always nearby.

The power of this approach is that it can make specialized care more accessible and affordable, while improving consistency in the quality of care and reducing safety risks in times of COVID-19. For patients, getting instant reassurance from an expert – rather than having to wait 1-2 weeks – also saves a lot of stress and anxiety.

In the future, one can even imagine a nurse performing a routine ultrasound exam at home or at a local retail clinic, using the kind of portable handheld device that already exists today, with an expert sonographer looking over the nurse’s shoulder remotely, and with AI extracting basic information from the scan. In the post-COVID-19 era, where patients will have come to expect convenient access to care close to home, this will open up entirely new pathways to diagnosis and treatment.

And it’s not just ultrasound that will become more widely available through remote guidance and education. In other imaging modalities, which face similar shortages of specialized staff, virtualization will also help to distribute expertise more evenly across locations and thereby improve access to care.

Virtual radiology makes specialized imaging more widely available

Unlike a handheld ultrasound device, we cannot take a 4-ton MR scanner into people’s homes. What we can do, however, is virtually connect imaging experts at a central hub – or what we call a Radiology Operations Command Center – with imaging technologists at scanners across care locations.

This cloud-based hub-and-spoke model enables real-time collaboration and over-the-shoulder support from expert users to their less experienced or specialized colleagues at remote sites, while the patient is on the scanner table. Not only does this help to standardize image quality, it can also make advanced imaging such as MR and CT accessible at more sites, closer to where patients live, at more flexible hours. In the future, such a command center could even operate across country borders, to support image acquisition wherever and whenever it’s needed.

Similarly, when it comes to the diagnostic interpretation of images, remote services will be critical for reaching underserved communities. In the past few months, teleradiology has proven to be particularly valuable in addressing backlogs in breast cancer screening, which was largely put on hold when the pandemic hit [5]. Especially in geographically challenged areas, where subspecialty radiologists are in short supply, having remote access to a dedicated women’s imaging specialist can make a huge difference in getting women their mammography results more quickly. And we know that turnaround times matter: the earlier we find a cancer, the better it is for patients, caregivers, and health systems alike.

A future of health for all

Of course, when it comes to such a complex challenge as improving access to care, technology is not an answer in and of itself. If there’s anything we’ve learned, it’s that building strong local partnerships and developing new business models is just as important. What’s so exciting about the virtualization of imaging is that, together, we can start reimagining care in completely new ways – by disseminating knowledge and integrating information across settings, all with the patient at the center.

Our ultimate hope is that every patient will have access to the same level of diagnostic sophistication and specialist care, whether that patient lives close to a specialized healthcare facility or hours away. We’re not there yet. But we’ve already made some big steps in the right direction. And with physical distances no longer being as big an impediment as they once were, that certainly brings the prospect of health for all a bit closer.

As part of our mission, we have an ambitious objective to provide access to care for the underserved, improving the lives of 400 million people a year in underserved communities by 2030. Click here to learn more about our Health Disparities program which embodies our social purpose of improving lives and access to care.

This article has been adapted from a previously published blog post on the global Philips News Center.

References

[1] Morris, M.A., Saboury, B. (2019). Access to Imaging Technology in Global Health. In: Radiology in Global Health, 15-33. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-98485-8_3

[2] World Health Organization (2019). Maternal mortality: key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

[3] Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) (2019). Improving Access to Maternal Health Care in Rural Communities. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/equity-initiatives/rural-health/09032019-Maternal-Health-Care-in-Rural-Communities.pdf

[4] Dagnan, N.S., Traoré, Y., Diaby, B., Coulibaly, D., Ekra, K.D., Zengbe-Acray, P. (2013). The use of ultrasound to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality in a primary care facility in Ivory Coast. Sante Publique, 25(1):95-100. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23705340/

[5] Naidich J.J., Boltyenkov A., Wang J.J., Chusid J., Hughes D., Sanelli P.C. (2020). Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Imaging Case Volumes. J Am Coll Radiol, 17(7):865-872.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.004